GI Cancer Incidence Is Increasing Among Younger Adults

Early-onset gastrointestinal (GI) cancers are defined as GI cancers diagnosed in individuals younger than 50 years. Globally, GI cancers represent the most rapidly increasing group of early-onset cancers, with colorectal cancer being the most common, followed by gastric, esophageal, and pancreatic cancers.i Similar trends are observed in the United States: between 2010 and 2019, GI cancers had the fastest-growing incidence rates among all early-onset cancers, with the steepest increases seen among individuals aged 30 to 39 years.ii The rising incidence of early-onset GI cancers signals profound gaps in public health and how the health system detects, diagnoses, and responds to cancer risk – revealing systemic failures in screening, symptom recognition and response, and public awareness and urgency.

Many early-onset GI cancers are diagnosed well before the standard screening age. For example, a substantial proportion of early-onset colorectal cancer cases occur among adults in their 20s, 30s and 40s, while the standard care guidelines recommend starting routine screenings at 45.iii,iv These screening guidelines largely determine when providers deliver – and insurers cover – routine cancer screenings. As a result, most young adults do not receive a cancer screening and early cancer symptoms are often attributed to benign or less serious GI conditions – resulting in longer intervals between symptom presentation and diagnosis.v,vi,vii

Beyond limited screening standards, rising incidence also appears to reflect increasing exposure to cancer risk factors that are not yet adequately addressed by existing prevention and early detection strategies and care guidelines, including ultra-processed diets, metabolic dysfunction, chronic inflammation and microbiome disruption, physical inactivity, and environmental exposures.viii Without more responsive, risk-based screening practices and stronger public awareness to improve care-seeking behaviors, populations will continue to experience advanced stage presentation at diagnosis, poorer survival, and reduced eligibility for clinical trials and precision medicine among young adults.ix,x

Early diagnosis goes beyond expanding screening age

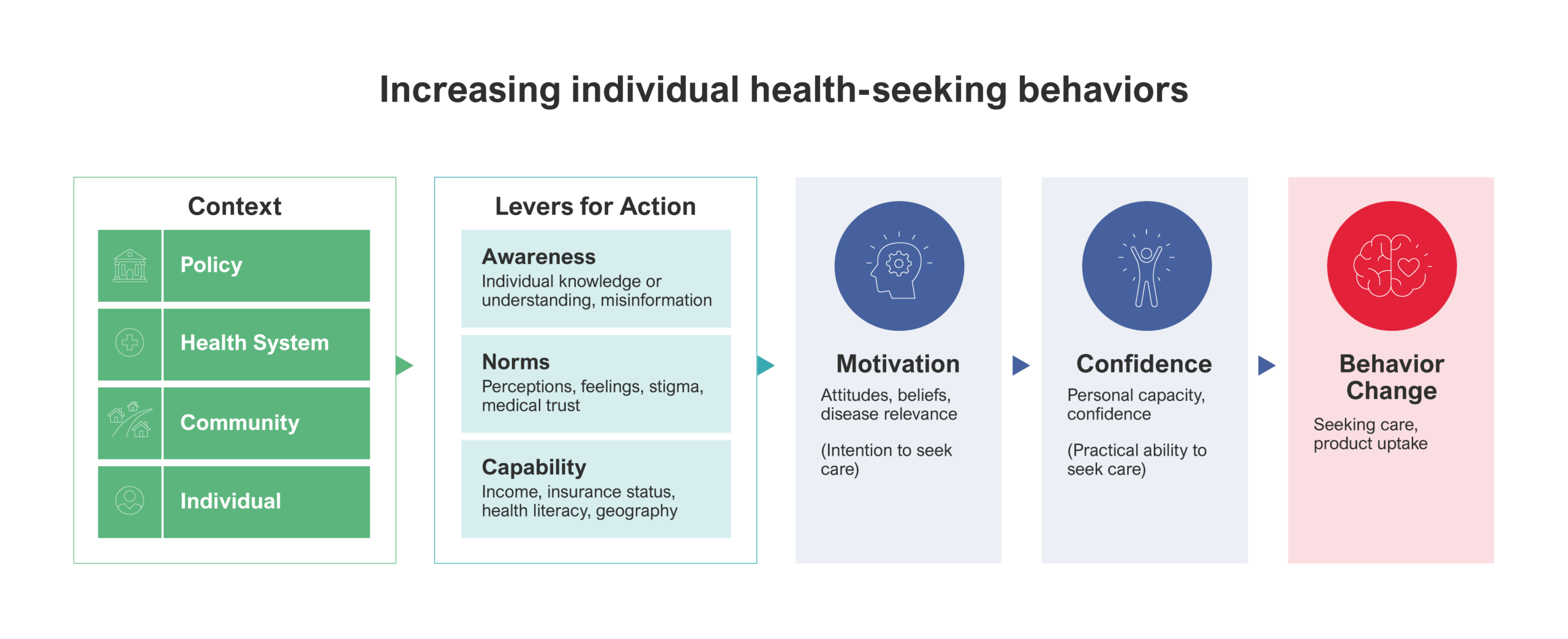

Efforts to increase early cancer diagnosis rates have traditionally focused on access, including expanding age-based screening thresholds, building diagnostic capacity within healthcare systems, and reducing patients’ financial and logistical barriers to care. While these interventions are essential, access alone cannot drive early cancer diagnosis – it also depends on individuals having the capacity to recognize early symptoms, seeking medical attention when necessary, and having the confidence and support needed to navigate the health system after initial presentation.xi

For early-onset GI cancers, low individual motivation – defined as low perception of risk and limited understanding of the value of seeking care – can help further explain why delays occur even before treatment decisions are initiated.xii As a result, reducing late diagnosis rates calls for interventions that extend beyond updating screening guidelines for at-risk adults, and includes a focus on increasing individual awareness and motivation to seek care, and building medical trust; alongside, addressing financial and logistical barriers to care.

This is a theory of change model created by Rabin Martin that adapts the 3 Cs of vaccine hesitancy – complacency, confidence and convenience – to the cancer context. Similar to the 3C model, it emphasizes that care-seeking behavior is shaped by more than access alone and requires similarly improving awareness and rebuilding trust and social norms to increase motivation to act and seek care.

Improving disease awareness to increase motivation to seek care

Low public awareness of GI cancer risk and early symptoms remains a central barrier to early diagnosis among younger adults. Many do not perceive themselves to be at risk for GI cancers due to public narratives that frame these diseases as conditions of older age. As a result, many early warning signs of GI cancers such as changes in bowel habits, stomach pain, bloating, indigestion, and acid reflux are often disregarded rather than prompting timely evaluation.xiii

Evidence suggests that disease awareness is more likely to prompt action when it feels personally relevant and is shared by trusted sources.xiv Community organizations, patient advocacy groups, survivors, and caregivers can help translate complex clinical information into accessible, patient-friendly materials that make it easier for individuals to understand their risk and recognize symptoms that warrant urgent attention and follow-up.

Shifting norms and building trust to increase willingness to seek care

Social norms, beliefs, and perceptions strongly influence when and how individuals seek care. For many people, decisions related to cancer screening and evaluation are shaped by trust in the healthcare system, fear of procedures or diagnosis, and cultural beliefs about illness and prevention. These factors can play a particularly important role among racial and ethnic minority communities, where lived experience, cultural context, and communication barriers often shape how cancer prevention and early care are understood and perceived – potentially discouraging early healthcare engagement amid negative belief systems.

In the context of colorectal cancer screening, research among African American communities has shown that low awareness of colorectal cancer risk, limited perceived benefit of screening, concerns about the invasiveness of colonoscopy, fear of pain, and lack of recommendation from a trusted healthcare provider all contribute to lower screening participation. Among Hispanic communities, cultural norms, distrust of the healthcare system, language barriers, and lower health literacy have been identified as particularly important influences on screening behavior – shaping whether individuals feel comfortable seeking preventive care.vii, xv

In Rabin Martin’s experience working in advocacy and supporting community-based partnerships, cancer prevention programs that are culturally tailored and delivered by trusted community members are most effective in increasing screening uptake. Community health advisors and peer leaders serve as credible messengers by relating to the experiences of the community, providing culturally appropriate education, addressing locally prominent fears and misconceptions, and directly guiding individuals through the screening process. Community-led, culturally grounded engagement can help rebuild trust and reshape care-seeking norms – empowering people to feel supported to act earlier across the care pathway.1

Improving individual capability to access a timely diagnosis

Even when individuals are motivated to seek care, socioeconomic factors and gaps in how healthcare is delivered can delay cancer diagnosis, particularly for younger adults and for racial and ethnic minority populations.xvi In a study of patients with early-onset cancers in the U.S., Asian, Black, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander individuals were significantly more likely to be diagnosed at an advanced stage than White patients.xvii Delays are often driven by lack of insurance or underinsurance, high out-of-pocket costs, long wait times for specialist referral and biopsy, and limited coordination across providers, all of which can slow progression from initial presentation to diagnosis.iv,xiii

Improving early diagnosis requires health systems and policies that respond to risk earlier and more consistently. Risk-based screening and referral approaches that incorporate age, family history, symptoms, and other risk indicators can help identify patients who warrant earlier evaluation outside traditional age thresholds, while coverage for diagnostic biomarker testing and navigation services can reduce drop-off along the care pathway.iv When systems are designed to act quickly on early warning signs, motivation to seek care is far more likely to result in timely diagnosis rather than delay.

Precision medicine in the context of early-onset cancer care

Precision medicine is an innovative approach to disease treatment and prevention that tailors strategies to an individual’s genetic, metabolic, environmental and lifestyle factors. xviii Yet, precision medicine tactics tend to primarily focus on biomarker testing and treatment, as opposed to early prevention intervention. For early-onset GI cancers, precision medicine offers a powerful opportunity to improve outcomes by enabling early risk identification, more precise diagnostic evaluation, and better coordination along the care pathway – provided patients enter care in time.xix For those diagnosed with GI cancer early in life, precision approaches include prevention and interception strategies that target the metabolic, inflammatory, and microbiome-related pathways increasingly linked to rising incidence, such as anti-inflammatory agents, metabolic interventions, and microbiome modulation.xx,xxi

Artificial intelligence (AI) can further strengthen precision medicine when embedded into routine care delivery. AI tools can detect relevant symptom patterns, stratify patient risk, predict disease onset, and support triage and coordinate care – helping clinicians identify patients who may warrant early evaluation and flagging delays in referral or testing.xxii

However, the promise of precision medicine ultimately depends on timely diagnosis and coordinated followup. When patients enter care late or experience prolonged diagnostic delays, eligibility for targeted and personalized treatment therapies and clinical trials are significantly reduced – narrowing the window in which precision approaches can deliver benefit.xxiii This, again, emphasizes the importance of increasing individual motivation and capacity to seek care early.

Translating Innovation into Earlier Care for Early-Onset GI Cancers

Ensuring that recent advances in cancer care improve outcomes for early-onset GI cancers will require more than scientific progress alone. Health systems must address barriers that delay diagnosis by strengthening navigation, early diagnostics, and coordinated referral pathways for younger adults. At the same time, patient-facing efforts are needed to improve symptom recognition, trust, and engagement so individuals enter care earlier. Aligning innovation with both system readiness and patient experience is essential to ensure advances in cancer care translate into better outcomes.

Footnotes

1 Through its proprietary ONPOINTTM Framework, Rabin Martin is able to lead and implement partnership and program strategies that are rooted in the community experience, co-created with trusted community partners and geared towards improving patient outcomes, building trust and driving long-term impact

End Notes

i Jayakrishnan, T., & Ng, K. (2025). Early-onset gastrointestinal cancers: A review. JAMA, 334(15), 1373–1385. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2025.10218

ii Koh, B., Tan, D. J. H., Ng, C. H., et al. (2023). Patterns in cancer incidence among people younger than 50 years in the US, 2010 to 2019. JAMA Network Open, 6(8), e2328171.https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.28171

iii Char, S. K., O’Connor, C. A., & Ng, K. (2025). Early-onset gastrointestinal cancers: Comprehensive review and future directions. British Journal of Surgery, 112(7), znaf102. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjs/znaf102

iv American Cancer Society. (2025). American Cancer Society Guidelines for Early Detection of Cancer.

v Castelo, M., Lima, A., Santos, J., Ribeiro, C., & Rocha, P. (2022).

Clinical delays and comparative outcomes in younger and older adults with colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Current Oncology, 29(11), 8609–8625. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol29110679

vi Mazidimoradi, A., Momenimovahed, Z., & Salehiniya, H. (2022).Barriers and facilitators associated with delays in the diagnosis and treatment of gastric cancer: A systematic review. Journal of Gastrointestinal Cancer, 53, 782–796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-021-00673-3

vii McGowan Hood. (2024, August 22).How younger cancer cases can spur misdiagnosis.

https://www.mcgowanhood.com/2024/08/22/how-younger-cancer-cases-can-spur-misdiagnosis/

viii American Journal of Managed Care. (2024). Rising incidence of young-onset cancer: Exploring the causes and generational risk factors. https://www.ajmc.com/view/rising-incidence-of-young-onset-cancer-exploring-the-causes-and-generational-risk-factors

ix American Association for Cancer Research. (2024). Treatment delays and survival divides by race, sex, and socioeconomic status. Cancer Research Communications. https://aacrjournals.org/cancerrescommun/article/6/1/235/772041/treatment-delays-and-survival-divides-race-sex-and

x Jerjes, W., & Harding, D. (2025).Breaking barriers: Enhancing cancer detection in younger patients by overcoming diagnostic bias in primary care. Frontiers in Medicine, 11, 1438402. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1438402

xi Okoli, G. N., Sanders, S., Myles, S., & Memon, A. (2021).Interventions to improve early cancer diagnosis of symptomatic individuals: A scoping review. BMJ Open, 11(11), e055488. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055488

xii Weinberg, B. A., Murphy, C. C., Freyer, D. R., Greathouse, K. L., Blancato, J. K., Stoffel, E. M., Drewes, J. L., Blaes, A., Salsman, J. M., You, Y. N., Arem, H., Mukherji, R., Kanth, P., Hu, X., Fabrizio, A., Hartley, M. L., Giannakis, M., & Marshall, J. L. (2025). Rethinking the rise of early-onset gastrointestinal cancers: A call to action. JNCI Cancer Spectrum, 9(1), pkaf002. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncics/pkaf002

xiii Health.com. (2024).Gastrointestinal cancers are on the rise among young people.

https://www.health.com/gastrointestinal-cancers-on-the-rise-among-young-people-11790633

xiv Ghio, D., Lawes-Wickwar, S., Tang, M. Y., et al. (2021). What influences people’s responses to public health messages for managing risks and preventing infectious diseases? A rapid systematic review of the evidence and recommendations. BMJ Open, 11(11), e048750. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-048750

xv Joo, J. Y., & Liu, M. F. (2021).Culturally tailored interventions for ethnic minorities: A scoping review. Nursing Open, 8(5), 2078–2090. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.733

xvi Yale Medicine. (2024). Early-onset cancer in younger people is on the rise.

https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/early-onset-cancer-in-younger-people-on-the-rise

xvii Taparra K, Kekumano K, Benavente R, et al. Racial Disparities in Cancer Stage at Diagnosis and Survival for Adolescents and Young Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(8):e2430975. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.30975

xviii Yale Medicine. (n.d.). Precision medicine. Yale School of Medicine. https://medicine.yale.edu/cancer/research/clinical/precision-medicine/

xix Yale Medicine. (n.d.). Precision medicine. Yale School of Medicine. https://medicine.yale.edu/cancer/research/clinical/precision-medicine/

xx Xu, Y., Zhang, L., Wang, H., & Li, J. (2025).Role of gut microbiome in suppression of cancers. Gut Microbes, 17(1), 2495183. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2025.2495183

xxi CURE Today. (2024).GLP-1 associated with colorectal cancer prevention, research finds.

https://www.curetoday.com/view/glp-1-associated-with-colorectal-cancer-prevention-research-finds

xxii Bhalla, S., & Laganà, A. (2022).Artificial intelligence for precision oncology. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology (Vol. 1361, pp. 249–268). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91836-1_14

xxiii Wijayanti, E., & Mahardhika, Z. P. (2024).Implementation of precision medicine in primary care: A struggle to improve disease prevention. Korean Journal of Family Medicine, 45(6), 359–361. https://doi.org/10.4082/kjfm.24.0165