Merging two parallel public health movements

Achieving Health Equity

The growing momentum behind ‘achieving health equity’ has scaled tremendously in the past several decades, originating from burgeoning efforts to eliminate health disparities. In recent years, through the COVID-19 pandemic, alongside the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests in the United States, the health equity movement has propelled forward, as these historical events were key inflection points in emphasizing the severity of health disparities and social injustices that existed between, and within, country geographies and their communities.

As a result, the public health landscape has witnessed sweeping reforms and action planning among health stakeholders – from public governmental agencies to large private businesses and small local community-based organizations – as they adapt their business strategies to consider their role in achieving health equity around the globe.

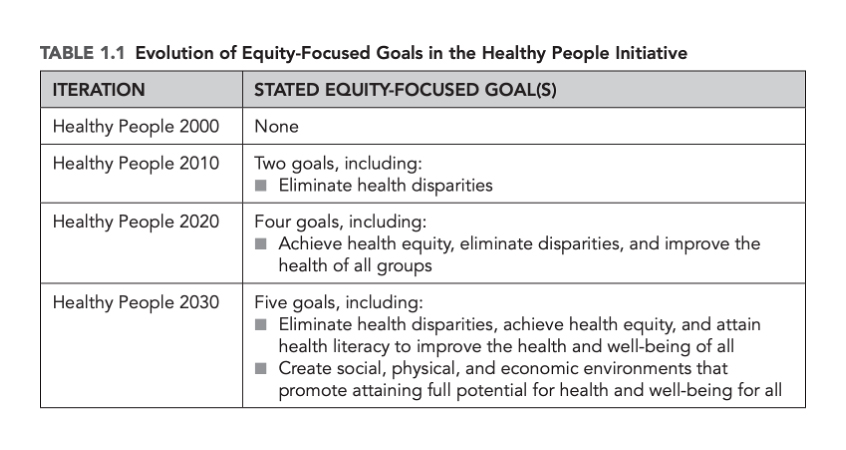

The multi-phase initiative from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS), Healthy People Initiative (2000, 2010, 2020, and 2030), offers a unique look into how the health equity movement has grown and evolved over time.[1]

For example, the first phase of the initiative, Healthy People 2000, launched in 1990, offered a general, broad-stroke, roadmap to achieving a healthy America for all – neglecting ‘health disparities’ as a key component to improving the health of Americans until the second phase of the initiative. Healthy People 2010 was transformative in its approach, as it accelerated the emerging field of health disparity research to allow ‘health equity’ nomenclature to come to the forefront of public health discussions.

It was only recently, under Healthy People 2030, launched in late 2020, that the HSS’ strategic roadmap finally outlined and prioritized methods focused on creating “social, physical and economic environments” to achieve health equity.[1]

Addressing the Climate Crisis

Alongside the escalated momentum set behind health equity, there has been a similar upswing in sustainability reform across industry markets, as public governmental agencies, including the European Union and U.S. Federal government, increased political regulations and mandates aimed at nudging economies and its stakeholders to make more climate conscious decisions. These mandates have pushed organizations across the private sector – including large biopharmaceutical companies, health foundations, and small-and-medium-sized enterprises, – to establish strategies aimed at identifying, preventing, mitigating, and accounting for the business’s climate change and sustainability risks (Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions). This has lead to the near the universal presence of “sustainable business initiatives” or “net-zero strategies” across the private market.i

As companies seek to set themselves apart from the status quo, some private organizations have voluntarily expanded their climate mitigation strategies to consider Scope 4 emissions – reducing downstream emissions of a product or innovation that occurs outside of a product’s life cycle or value chain but are a result of the use of that product.ii

While the momentum set behind these important global efforts is encouraging, these movements remain tangential to each other. The siloed approach to health equity and sustainability neglects the blossoming, and health-critical, opportunity to prioritize environmental drivers of health* – the foundation of environmental justice and the white space that exists at the nexus of these two movements. As climate change gradually intensifies, and remains the greatest threat to human health, a focus on the environment, and its impact on health and health systems, is rising as a business-critical priority for the private health sector and its approach to protecting human health.

Environmental justice is essential if we are to achieve health equity

The concept of environmental justice originates from the civil rights activist, Dr. Benjamin F. Chavis Jr., in the early 1980s after the state of North Carolina dumped soil laden with cancer-causing chemicals in a low-income Black farming community. Dr. Chavis defined the antithesis of environmental justice as ‘the intentional siting of polluting and waste facilities in communities primarily populated by Black, Hispanic, Indigenous People, Asian American and Pacific Islanders, migrant and low-income workers.’ Modern day examples of what is defined as environmental racism includes the water crisis in Flint, Michigan as well as Cancer Alley in Southern Louisiana.

Research has shown that low-income and racial and ethnic minority communities are disproportionately exposed to hazardous toxins, carcinogens, pollutants and unsafe community environments that increase risk of health challenges, including respiratory illness and cancer alongside rising rates of morbidity that complicate non-communicable disease management. Especially as the global population increasingly experiences the harmful impacts of a climate changed, and changing, world, the narrative of environmental discrimination is a common, and growing, story across country and community contexts.

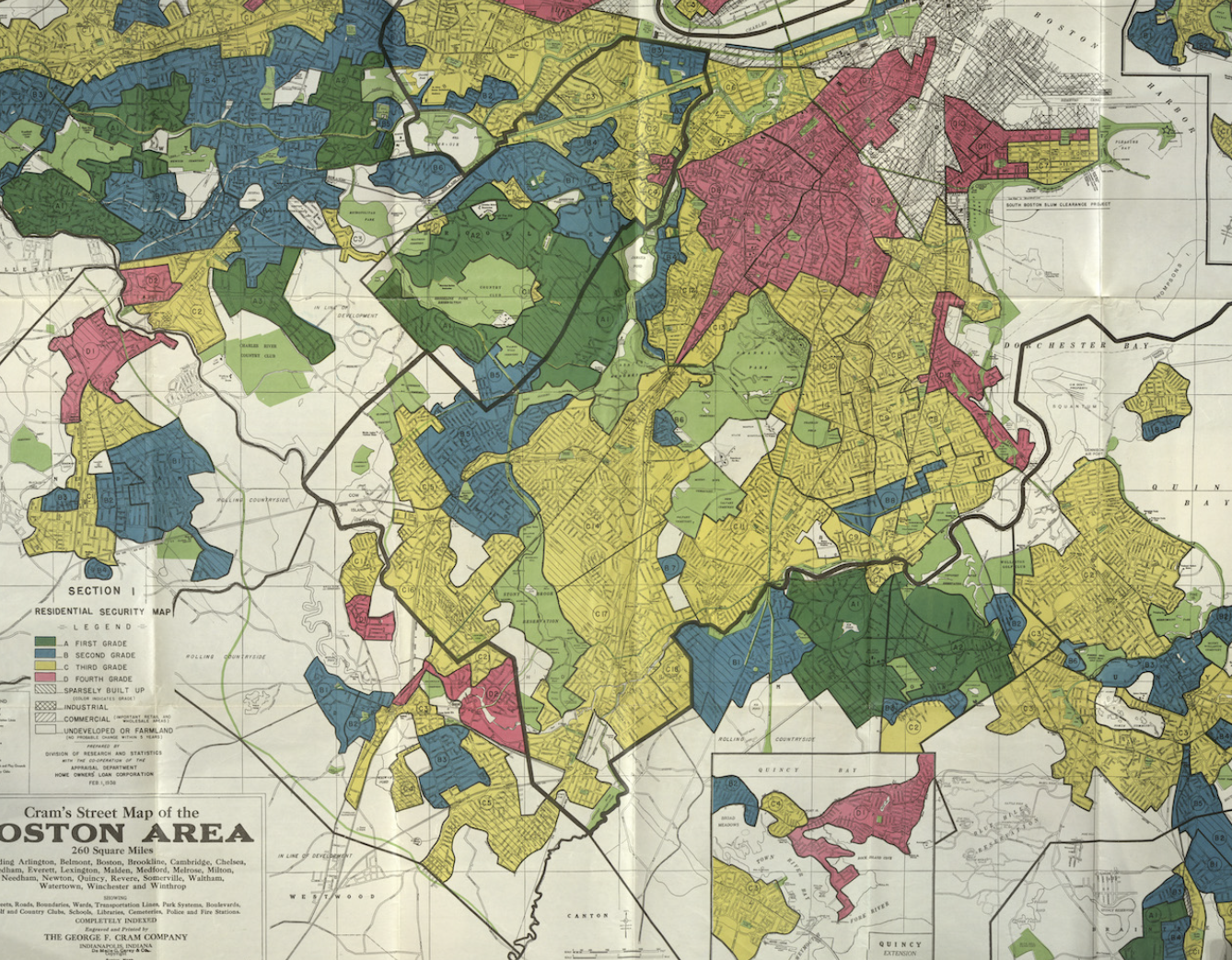

In the Environmental Racism in Greater Boston research series, experts from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health showcase how racial residential segregation and neighborhood environmental disparities – air, water and soil pollution, proximity to pollution sources, green space and urban heat – are creating long-term health problems among low-income and racial/ ethnic minority populations. The research narrative notes similar narratives can be told across the global community.2

Therefore, it is essential for public health and health equity strategies to start considering all components that drive health disparities – including the regularly neglected environmental risk factors alongside the regularly prioritized social and economic risk factors. It will be impossible to achieve health equity in this new climate changing world without a transformative and comprehensive approach to public health – not only recognizing the environment’s increasing and variable impact on health, but also acknowledging how environmental factors limit, or directly impede on, other social initiatives that seek to bridge access to health care and improve health outcomes across the patient journey (prevention to treatment and beyond).

While there are multiple community-based organizations who have taken the initiative to address environmental discrimination and risk factors amid limited aid from their public health care system – including Rise St. James in Cancer Alley and the Environmental Transformation Movement of Flint – these organizations are chronically under-funded, under-resourced and de-prioritized within private health investment and social responsibility strategies.

In order to effectively protect human health, meet evolving health care demands, optimize reach and achieve business goals, the private health sector needs to consider and adapt its business practices to respond to the multi-pronged impact the environment, and climate change, has on health systems and population health. Otherwise, company strategies remain at risk of a growing blind spot that will increasingly disrupt business practices, prevent engagement in large-scale business opportunities, and limit the reach, need, and/or efficacy of products and services across high and low-income countries alike.

Understanding our climate changed, and changing, world

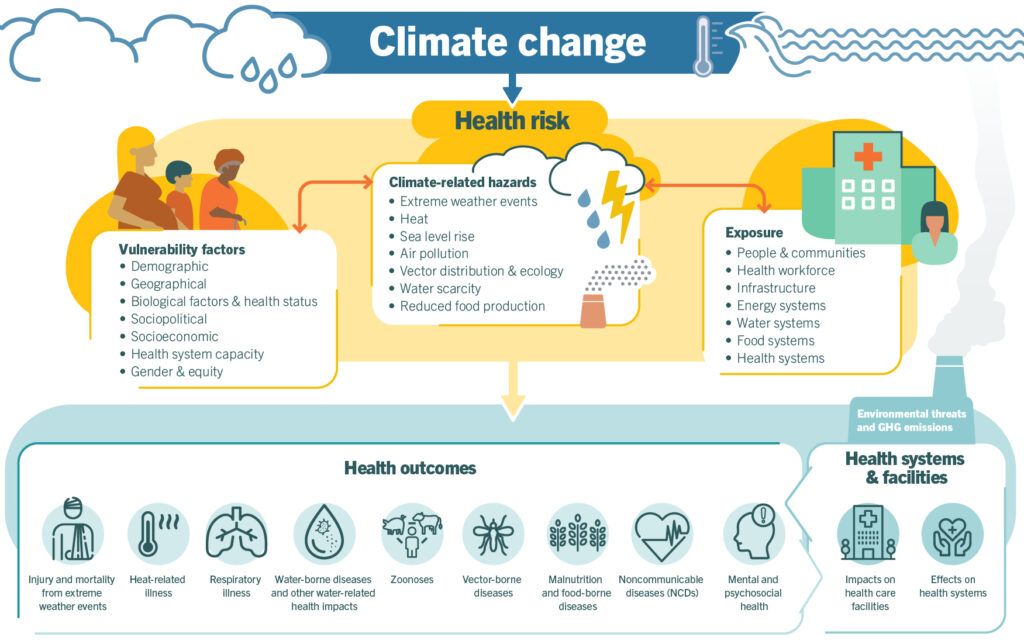

Climate change not only affects the physical environment but also affects all aspects of a community ecosystem, including social and economic conditions and the functioning health, and health adjacent, systems like food, transportation, and energy.

Many multilateral and global public health agencies have attempted to develop infographics that illustrate the complex and myriad of ways climate change impacts health across all countries contexts. However, it’s important to note that low-and-middle-income countries remain most vulnerable to climate change and environmental risk factors, further exacerbating disparities among women and children and ‘last mile’ residents.

Source: WHO, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health

Climate change threatens a multiplier effect that is set to reverse decades of health progress – giving rise to more, and new, cancers, setting cancer to becoming the leading cause of death worldwide in the 21st century;iii exacerbating incidence of epidemics and pandemics; increasing rates of co-morbidities and mortality among those with non-communicable disease like cardiovascular disease; disrupting health care systems, including supply chains; preventing millions of girls from completing their education in lower-and-middle income countries;iv becoming a top driver of conflict and humanitarian crisesv … each outcome shifting the public health landscape and forcing health stakeholders to cyclically forecast, adapt, innovate, evaluate and re-adapt to effectively reach populations and address evolving short and long-term health needs and demands.

What’s next: Addressing the ‘sustainability for health equity’ opportunity

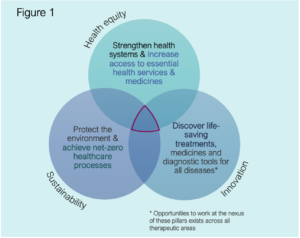

In summary, the private health sector – through adapted internal business practices, expanded partnerships and holistic health care strategies – needs to acknowledge this new inflection point and lead the next movement in public health. A movement that drives and scales high-impact initiatives and strategies that recognize the interconnectivity of community health ecosystems, understand the duplicative impact of environmental and social injustices, and seek to work at the nexus of sustainability, health equity and innovation [figure 1]. Rabin Martin commits to leveraging our deep experience and breadth of expertise to help private organizations across sectors – including within health and health adjacent – identify opportunities that protect and propel the business forward by responding to the short- and long-term needs of society, health systems and the planet.

As an emerging field, participation requires a cyclical approach to innovation by testing, learning, adapting, and building on best practices. As an essential stakeholder in the health care ecosystem, the private sector can initially lean into its strengths to contribute in a way that provides value to the business and effectively responds to shifting population health care needs, while also complementing others’ efforts.

- Conduct research to quantify how the environment and climate change impacts health outcomes across therapeutic areas – informing, and future-proofing, health care and business strategies

- Strengthen global and local supply chain resiliency, including heat-stable product development, to respond to shifting disease patterns and climate vulnerabilities – preventing stock-outs and ensuring undisrupted access to essential, high-quality, medicines

- Build a sustainable and climate-responsive value chain from clinical trial design to market access – decarbonizing healthcare, maximizing use of resources, eliminating waste production and effectively and ‘greenly’ reaching all patients

- Equip health care workers to be at the frontline of climate response – educating and keeping patients connected to health services across the care journey

- Support ‘health in all’ advocacy initiatives driven by those most impacted by climate change and environmental injustices, especially youth – building a policy environment that ensures the business, and its programs, effectively and sustainably reach all patients with the services and medicines they need most

- Scale digital technologies, including artificial intelligence to increase access to predictive health care solutions and improve the accuracy and efficiency of care services – decarbonizing health systems while scaling delivery of timely and quality care and emergency response

- Establish collaborative and innovative partnerships that seek to build safe, clean, and health promotive environments – addressing modifiable risk factors and reducing vulnerabilities across the community ecosystem to holistically improve health outcomes and prevent disease

Rabin Martin recognizes that the success of integrated health strategies and programs are dependent on addressing the risk factors that are most relevant to the local community ecosystem. In collaboration with our clients, we co-design integrated and place-based solutions that seek to transform where people live, to transform how they live across the life course.

*Inclusive and empowering language is important – Research has found that the term “’determinants’ of health” is regularly perceived as ‘confusing, alienating and/or demeaning’ among the general population, as the term directly suggests specific social, economic and environmental risk factors will “determine” someone’s health – removing perceptions of having autonomy or agency to change or address these factors to improve health. Alternatively, “‘drivers’ of health” holds a more open connotation – offering the opportunity and capacity to change the trajectory of these risk factors to protect and promote health and well-being across the life course. Another interesting way to think about it is by replacing ‘health’ in “determinant of health” with “death” – social determinant of death feels daunting and finite, while social driver of death feels as though there is an opportunity to proactively adapt or change direction to avoid, and/or prevent, death.

1 Health Equity: Overview, History, and Key Concepts

2 Interactive web series explores environmental racism | News | Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

i Overview of sustainable finance – European Commission (europa.eu)

ii We know Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions. But what are Scope 4? | World Economic Forum (weforum.org)

iii Climate Change Will Give Rise to More Cancers | UC San Francisco (ucsf.edu)

iv Malala Fund. (2021). Change the Subject: How leaders can take action for climate education at COP26. https://malala.org/newsroom/malala-fund-publishes-report-on-climate-change-and-girls-education

v United Nations. The climate crisis is a humanitarian crisis. https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/the-climate-crisis-is-a-humanitarian-crisis